Aftermath

(from Picture-Show)

HAVE you forgotten yet?...

For the world's events have rumbled on since those gagged days,

Like traffic checked while at the crossing of city-ways:

And the haunted gap in your mind has filled with thoughts that flow

Like clouds in the lit heaven of life; and you're a man reprieved to go,

Taking your peaceful share of Time, with joy to spare.

But the past is just the same--and War's a bloody game...

Have you forgotten yet?...

Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you'll never forget.

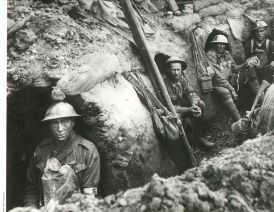

Do you remember the dark months you held the sector at Mametz--

The nights you watched and wired and dug and piled sandbags on parapets?

Do you remember the rats; and the stench

Of corpses rotting in front of the front-line trench--

And dawn coming, dirty-white, and chill with a hopeless rain?

Do you ever stop and ask, 'Is it all going to happen again?'

Do you remember that hour of din before the attack--

And the anger, the blind compassion that seized and shook you then

As you peered at the doomed and haggard faces of your men?

Do you remember the stretcher-cases lurching back

With dying eyes and lolling heads--those ashen-grey

Masks of the lads who once were keen and kind and gay?

Have you forgotten yet?...

Look up, and swear by the green of the spring that you'll never forget.

War Poetry of World War I

RUPERT BROOKE

WILFRED OWEN - (1893-1918)

Photo 1916

Anthem for Doomed Youth

by Wilfred Owen

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

-- Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, --

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

September-October 1917

THE SOLDIER

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Rupert Brooke (1887-1915)

BACK TO THE WORLD WAR ONE PAGE

Mud and Rain

By Siegfried Sassoon

Mud and rain and wretchedness and blood.

Why should jolly soldier-boys complain?

God made these before the roofless Flood -

Mud and rain.

Mangling cramps and bullets through the brain,

Jesus never guessed them when He died.

Jesus had a purpose for His pain,

Ay, like abject beasts we shed our blood,

Often asking if we die in vain.

Gloom conceals us in a soaking sack --

Mud and rain.

Siegfried Sassoon survived the Great War, but he continued to re-visit the trenches in his poetry and pose for the rest of his life. He couldn't forget his experiences, but he feared that most of us would. He died in 1967.

Dulce Et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on , blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tried, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!--An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,--

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Survivors -

Siegfried Sassoon

NO doubt they’ll soon get well; the shock and strain

Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk.

Of course they’re ‘longing to go out again,’

These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk.

They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died,

Their dreams that drip with murder; and they’ll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter’d all their pride...

Men who went out to battle, grim and glad;

Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad.

BBC World War I site - Shell Shock

SHELL SHOCK - Heritage of the Great War site. - NOTE: to find the article on Shell Shock you must scroll down the links in the left-hand pane until you reach the article called: "Unforseen Epidemic of Shell Shock" (about 20-25 articles down) - you should also check out the article called "Shot at Dawn in the Dunes of Flanders" - great article!

In the early months of the Great War almost all of the poetry had a positive outlook. Like the earlier poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson, (The Charge of the Light Brigade) it tended to focus on Patriotic themes and the "Glory" of battle. Rupert Brooke's poem - "The Soldier" is a good example. Unfortunately for Brooke, he became ill while training for the Gallipoli campaign and died before ever seeing combat.

Some of Britain's best poets served in the Great War. Of these, one of the most famous was Siegfried Sassoon. He too, at first wrote patriotic poems about the war, but as time went on he became greatly disillusioned with the war, especially after his brother was killed at Gallipoli in 1915. His poetry took on a somber, and bitter tone. Shocked by the misery of trench existence and the ever increasing casualties experienced in battle, he began to paint a picture of the horrors and misery of war. His poems took on a sarcastic & critical tone as he witnessed thousands of young men's lives ended or ruined by the brutality of modern war, and the apparent callousness of the military and civilian leadership.

The poem below - "Mud and Rain" is a good example:

Does it Matter?

Siegfried Sassoon

(from Counter-Attack)

DOES it matter?--losing your legs?...

For people will always be kind,

And you need not show that you mind

When the others come in after hunting

To gobble their muffins and eggs.

Does it matter?--losing your sight?...

There's such splendid work for the blind;

And people will always be kind,

As you sit on the terrace remembering

And turning your face to the light.

Do they matter?--those dreams from the pit?...

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won't say that you're mad;

For they'll know you've fought for your country

And no one will worry a bit.

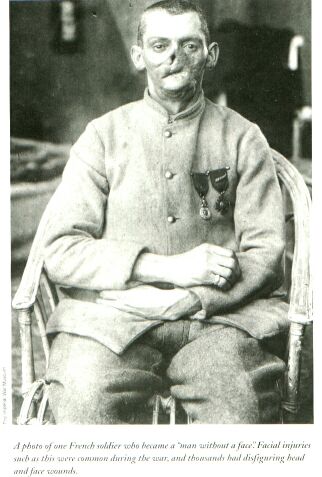

A French soldier who became a "man without a face". Facial injuries such as this were common during the Great War.

Victims of Mustard Gas.

Sassoon's Declaration against the War

"I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that this War, on which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purpose for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them, and that, had this been done, the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation. I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust. I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed. On behalf of those who are suffering now I make this protest against the deception which is being practised on them; also I believe that I may help to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the contrivance of agonies which they do not, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realize".

Suicide in the Trenches

by Siegfried Sassoon

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you'll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

Before long, Sassoon became convinced that the political leadership of the Allies had changed the goals of the war. He believed it had become a "war of conquest" rather than a defensive war or a war of liberation. He decided that he should protest the way the war was being conducted by publishing an anti-war statement. Sassoon was a much-respected and celebrated poet and a decorated war hero. He expected to be courts-martialed for his protest and hoped that the publicity would wake up the people back home to the horrors of the war and help them to realize that they were being lied to by those who had the political power. Moreover he believed that his actions would somehow convince the people in power to end the war and negotiate a peace settlement.

Instead of being courts-martialed, Sassoon was declared to be suffering from "Shell Shock", and was sent to the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland.

While at Craiglockhart under the care of Dr. W.H.R. Rivers, Sassoon met a young soldier-poet named Wilfred Owen who was being treated for Shell Shock. Owen had been found in a shell hole where he had spent 48 hours in the company of the dismembered corpse of a friend. While they were in treatment, Sassoon read some of Owen's poems and encouraged Owen to write about his experiences in the war and his attitudes toward the war.

While in treatment at Craiglockhart, both Owen and Sassoon began to feel guilty that they were living in relative safety while their men were still suffering & dying in the trenches of the Western Front. Both men decided to return to the front to be with the men they led in combat.

Sassoon was shot in the head, but survived. Owen however was killed while leading his men on a raid across a canal. Owen died November 4, 1918 - just one week before the war ended.

After the war, Sassoon worked to get Owens poems published.

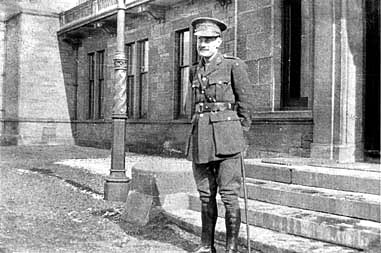

Dr. W. H. R. Rivers

Chief Medical Officer

Craiglockhart War Hospital

Edinburgh, Scotland

Craiglockhart War Hospital treated officers for "Shell Shock"

The story of Sassoon & Owen and their treatment at Craiglockhart is masterfully told in a 1997 film entitled "Behind the Lines" directed by Gillies MacKinnon and based on the 1991 book entitled "Regeneration" by Pat Barker. "Regeneration" was the 1st book in Barker's trilogy about World War I.

The Parable of the Old Man and the Young - Wilfred Owen

So Abram rose, and clave the wood, and went,

And took the fire with him, and a knife.

And as they sojourned both of them together,

Isaac the first-born spake and said, My Father,

Behold the preparations, fire and iron,

But where the lamb, for this burnt-offering?

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

And builded parapets and trenches there,

And stretchèd forth the knife to slay his son.

When lo! an Angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not they hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him, thy son.

Behold! Caught in a thicket by its horns,

A Ram. Offer the Ram of Pride instead.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.

Owen's "The Parable of the Old Man and the Young" is an angry parody of the Biblical story of Abraham & Isaac (GENESIS 22, 1-19). He intentionally uses archaic words such as "spake" and "clave" to give the story a more biblical feel. It clearly shows Owen's anger toward the world's leaders who were willing to sacrafice their country's youth for the sake of pride & patriotism.

The words "Dulce Et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori" are Latin and mean "it is sweet and proper to die for one's country." This phrase was widely used back home by patriotic teachers in the public schools at the start of the Great War.

Owen's poem "Dulce Et Decorum Est" is one of the finest examples of war poetry ever written.

The Death-Bed – Siegfried Sassoon

He drowsed and was aware of silence heaped

Round him, unshaken as the steadfast walls;

Aqueous like floating rays of amber light,

Soaring and quivering in the wings of sleep.

Silence and safety; and his mortal shore

Lipped by the inward, moonless waves of death.

Someone was holding water to his mouth.

He swallowed, unresisting; moaned and dropped

Through crimson gloom to darkness; and forgot

The opiate throb and ache that was his wound.

Water—calm, sliding green above the weir.

Water—a sky-lit alley for his boat,

Bird- voiced, and bordered with reflected flowers

And shaken hues of summer; drifting down,

He dipped contented oars, and sighed, and slept.

Night, with a gust of wind, was in the ward,

Blowing the curtain to a glimmering curve.

Night. He was blind; he could not see the stars

Glinting among the wraiths of wandering cloud;

Queer blots of colour, purple, scarlet, green,

Flickered and faded in his drowning eyes.

Rain—he could hear it rustling through the dark;

Fragrance and passionless music woven as one;

Warm rain on drooping roses; pattering showers

That soak the woods; not the harsh rain that sweeps

Behind the thunder, but a trickling peace,

Gently and slowly washing life away.

He stirred, shifting his body; then the pain

Leapt like a prowling beast, and gripped and tore

His groping dreams with grinding claws and fangs.

But someone was beside him; soon he lay

Shuddering because that evil thing had passed.

And death, who'd stepped toward him, paused and stared.

Light many lamps and gather round his bed.

Lend him your eyes, warm blood, and will to live.

Speak to him; rouse him; you may save him yet.

He's young; he hated War; how should he die

When cruel old campaigners win safe through?

But death replied: 'I choose him.' So he went,

And there was silence in the summer night;

Silence and safety; and the veils of sleep.

Then, far away, the thudding of the guns.

French monument - Beaumont Hamel

The Battle of the Somme 1916

Wilfred Owen, a 24 year old British officer and poet, went off to war writing verses about glory and sacrifice. Like Sassoon, he too became disillusioned by the horrors of war. He came to resent the patriotic talk on the home front of the "Glories of war - of Sacrafice for King and Country".

Base Details

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967). Counter-Attack and Other Poems. 1918.

IF I were fierce, and bald, and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet Majors at the Base,

And speed glum heroes up the line to death.

You’d see me with my puffy petulant face,

Guzzling and gulping in the best hotel,

Reading the Roll of Honour. ‘Poor young chap,’

I’d say—‘I used to know his father well;

Yes, we’ve lost heavily in this last scrap.’

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I’d toddle safely home and die—in bed.

The Hero

Siegfried Sassoon, 1917

'Jack fell as he'd have wished,' the mother said,

And folded up the letter that she'd read.

'The Colonel writes so nicely.' Something broke

In the tired voice that quivered to a choke.

She half looked up. 'We mothers are so proud

Of our dead soldiers.' Then her face was bowed.

Quietly the Brother Officer went out.

He'd told the poor old dear some gallant lies

That she would nourish all her days, no doubt

For while he coughed and mumbled, her weak eyes

Had shone with gentle triumph, brimmed with joy,

Because he'd been so brave, her glorious boy.

He thought how 'Jack', cold-footed, useless swine,

Had panicked down the trench that night the mine

Went up at Wicked Corner; how he'd tried

To get sent home, and how, at last, he died,

Blown to small bits. And no one seemed to care

Except that lonely woman with white hair.